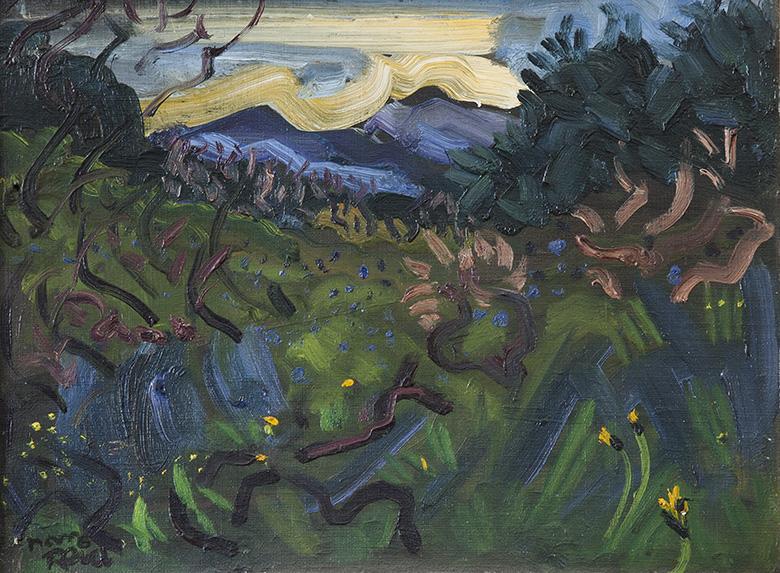

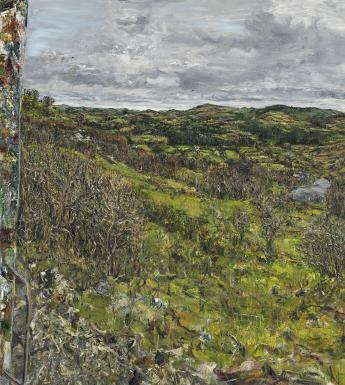

Shaping Ireland: Landscapes in Irish Art is our latest exhibition, exploring the relationship between people and the Irish landscape, as visualised by artists over 250 years. As part of the fully illustrated catalogue accompanying the exhibition, we invited a number of experts to write their responses to the theme of 'Shaping Ireland'.

The following is the response by ecologist Pádraic Fogarty, called Lights Out - Ireland & Mass Extinction. Pádraic is the Campaign Officer with the Irish Wildlife Trust.

Growing up to three metres long, the sturgeon is a massive fish. Its plate-like scales, slightly upturned snout and moustache-like ‘barbels’ (feelers) lend it a slightly aristocratic air – like a medieval knight ready to ride into battle. The sturgeon was once reasonably common around Irish coasts, breeding in deep estuaries and slow-moving rivers like the Barrow and Liffey, even featuring on the menu of the monks at their abbey along the mighty River Shannon at Clonmacnoise. The fish can live a long time, are slow to reach maturity and don’t rear many young – a combination of traits that left it vulnerable to threats such as overfishing, habitat loss and pollution. Nets set for trapping salmon on their annual migrations are likely to have taken a heavy toll so that by the early 1900s reports were fewer and fewer. The last confirmed sighting of a sturgeon in Ireland was 1967, when a 29 kg fish was caught off the coast of Cork.

The extinction of this ‘Royal Fish’ (since the Middle Ages all sturgeon have been technically the property of the English Crown) went largely unnoticed. There was no outcry from conservation bodies, no action plans to halt its demise, no funeral dirges were sung to mark its vanishing.

The American author John Steinbeck, in his novel The Winter of our Discontent, wrote that ‘it’s so much darker when a light goes out than it would have been if it had never shone’. And so it was, with the extinction of the sturgeon from Irish waters a light went out in the natural world. And it has not been the only one – since the arrival of humans in Ireland the extinction of around 120 species of plant and animal has been documented, while many more are likely to have flickered out without anyone noticing. Indeed, so many lights have gone out that a darkness has descended across the natural world on our small island.

According to the National Biodiversity Data Centre, around 3,000 species have been assessed by scientists and anywhere from a quarter to a third are threatened with extinction. Whole ecosystems have been swept away by the march of progress, from the once-famous raised bogs of the Midlands (0.6% of which remains intact), native woodlands (which cover only about 1% of the land), to the seas which have been trawled to oblivion, resulting in massive overfishing and destruction of marine food

webs. As industrial farming extracts more from the land, so one third of our bees face extinction and over half our rivers and lakes are polluted.

Once-common and abundant species like the curlew, the freshwater pearl mussel, the Atlantic salmon and the European eel are now greatly diminished or hang on only in isolated corners. Yet as the lights of life dim, so our eyes become accustomed to the darkness. The sea looks largely as it did a millennium ago, the green fields still roll off to the distance, the open-cast peat mines are hidden down country lanes. Nobody misses the snooty sturgeon drifting in the muddy depths. The greatest mass extinction of life on planet Earth in over 60 million years, and which has affected Ireland perhaps more than any country, largely goes unnoticed.

Pádraic Fogarty, 2019

The exhibition catalogue has many more responses to the theme of Shaping Ireland, including works by Paula Meehan (poet), Mary Reynolds (landscape designer), Duncan Stewart (environmentalist) and John Tuomey (architect), among others.Shaping Ireland: Landscapes in Irish Art was on view 13 April to 7 July 2019.Friends of the Gallery go free. |

You might also like:

-

Podcasts: The Island, A Prospect

Listen back to our podcasts about Ireland and art

-

The Colour of Ireland

If the glossy green of Ireland is the result of man-made chemical

-

The Island, A Prospect - a poem by Paula Meehan

A poem by Paula Meehan, written in response to the exhibition Sha

-

Shaping Ireland: Landscapes in Irish Art

13 April – 7 July 2019